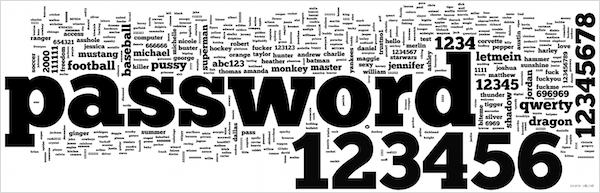

Password Security

- 4.7% of users have the password password

- 8.5% have the passwords password or 123456

- 9.8% have the passwords password, 123456 or 12345678

- 14% have a password from the top 10 passwords

- 40% have a password from the top 100 passwords

- 79% have a password from the top 500 passwords

- 91% have a password from the top 1000 passwords

If you go to a friend’s Facebook account right now, you quite possibly have a 1 in 20 chance of guessing it first time if you know what to guess. Now consider that there is a very good chance they use the same password for their email, their online shopping, their bank.

Now the numbers may be a bit exaggerated in this case: the statistics come from a few years ago when a hacker breached security of RockYou, a social photo sharing sort of service, I realise that the numbers will probably not accurately represent password selection for online banking for example. However very few people know what it really takes to make a secure password, and even fewer know how long it would take to break their password. Because of this, while people may not use ‘123456’ for their online banking, they may be using something which isn’t a lot better.

There are 2 main factors that I think need to be taken into account when constructing a password: human guessability and machine guessability.

Human Guessability

This is really quite simple, and in fact the one that people are getting better at counteracting. It’s quite simple: don’t use predictable words and phrases. Don’t use your dog’s name or your child’s birthday, or your number plate (yes, people do). A good password has absolutely nothing to do with you. Yes they might be easier to remember in the short term, but in reality you probably type your password at least once a day, come up with something random and you will learn it very quickly.

The other related idea here is using the same password on more than one account/service/website/etc. Almost everyone does this in some form because it’s difficult to remember so many passwords (I have saved passwords for 244 different websites) so this is only natural, but it also means that if someone has your password for one service they may well get access to others, and things like your email account can give away so much sensitive information that this could be disastrous.

Machine Guessability

This is just a matter of speed. There are 2 ways for computers to ‘hack’ passwords, dictionary attacks and brute-force attacks. Dictionary attacks use a set of words to guess, often taken from a dictionary, or from a set of words that have something to do with the person who’s password is being attacked. A clever hacker using a dictionary attack might also add to the dictionary a list of common passwords. Brute-force attacks take far longer as they basically try every combination of characters in the character set being used.

The key therefore to making password unguessable to computers is to make sure they are long and do not contain words. Simple right? Not really. You see in computing there is something called Moore’s Law which states that every 18 months the number of transistors available on processors will double. This essentially means that a computer for a given price will be twice as fast as one for the same price 18 months previously[2].

Computers are getting faster, and will continue to do so for many years to come, so we need to plan for this in the passwords we use. Contrary to what the little suggestions next to password boxes on websites may say, a minimum of 6, 8 or even 10 characters is not enough any more, and adding numbers and punctuation makes little difference. If you password will take 10 years to crack now, but in 5 years time it will only take 4 months to crack, and in 10 years time it would only take 3 days. A hacker might not bother cracking you password now, but in the future it may well be worth it for the relatively short amount of time it would take.

Maybe you won’t have the same password for 10 years, it is after all a fairly good idea to change passwords regularly, but I know I still have some passwords that are 7 years old that I haven’t gotten around to changing yet, and also you would be surprised how many passwords can be cracked in a lot less than 10 years even on today’s computers.

So What is a Good Password?

I suggest using a password ‘formula’. Have a standard section of password that you use, and then add to it something based on the particular service you are using, perhaps something like this:

The rule is really quite simple to learn, and you can come up with anything you like to obfuscate the letters of the service name. Also, you might think that marlejfufmickarroty would be difficult to learn, but you would be surprised how quickly you can, and for the extra security, it is really worth it.

Other things you can do to protect your accounts is to use incredibly long and very random strings like 5tjVk455X6}6wJr7qhr5Z’cl;c1LdY)xYmWvyF?a_@1cxB-oog for your passwords and leave all of the remembering up to a password manager. Applications such as 1Password and Last Pass can generate passwords for you and remember them so you never have to type them in. However a database like that is only as secure as the password you put on it, which, given the data contained inside, is far more critical. Also there is the issue that without those apps or their databases you have no access to any of your accounts, you need to rely on always having the database on your device.

How Good is My Password?

So many of the password strength indicators online are really bad at indicating strength correctly. They look at whether you have punctuation and numbers and don’t give that much credit to the number of characters. jquery.complexify.js is a jQuery library designed to implement just this.

Conclusions

Hopefully you can see from this that it is the number of characters in a password that makes all the difference, and using a 15 character password rather than 8 characters will give your account much better protection. There are many things I have left out of this article, in particular discussion of whether all of this is necessary as to fully explain the issues you need a good knowledge of the ways in which services store passwords. Perhaps I will do that in another article, but for now I think it is enough to say that if you have a weak password you are putting a lot more trust on the service provider, and as we have seen with the RockYou hack, Playstation Network hacks, and others that have been in the news recently, that may not be a good idea.

This is debateable. It varies between being every 1 year and 2 years, and is thought to be slowing down, and linking it to price is a simplification because there are many other components in a comptuer the contribute to speed. I do however think this is a pretty good approximation.

The numbers in this example are the result of a bit of research into machines suitable for brute-forcing, and their relative hashes-per-second, but this should not be taken as literal. The numbers are based on SHA1 hashing.

- Home PC: average CPU and a Nvidia GTX 260.

- Amazon EC2 Instance: high speed server CPUs and 2x Nvidia Tesla M2050 cards.

- Custom Password Brute-Forcing Computer: 25x ATI/AMD Radeon HD6990 (Article on Ars Technica).

The prices that I quote were approximately correct at the end of 2011.