Unlocking Hillsborough

I’m writing this on the train home from Rewired State’s latest event: National Hack the Government Day 2013 (event summary page). It was another great event with the same friendly atmosphere that goes along with so many (especially Rewired State’s) developer events. My friend Elliot and I won in one of the categories, and so this post is mostly about what we did, how we did it, and why we think it’s important.

You can find Elliot’s writeup of the hack on his blog.

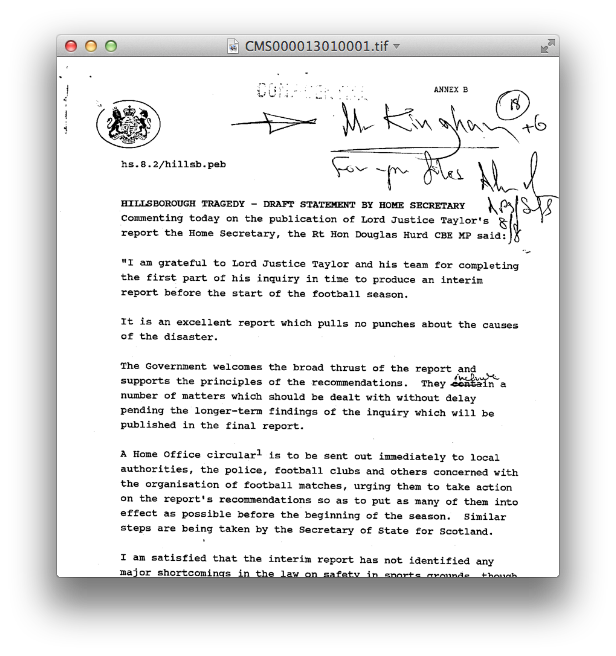

One of the new datasets that was released shortly before the hack day, and which we were all encouraged to use was the archive of documents from the Hillsborough enquiry.

The 1989 Hillsborough disaster was an incident which occurred during the FA Cup semi-final match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest football clubs on 15 April 1989 at the Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield, England. The crush resulted in the deaths of 96 people and injuries to 766 others. The incident has since been blamed primarily on the police. The incident remains the worst stadium-related disaster in British history and one of the world’s worst football disasters.

The inquiry has apparently embraced open data, and has made a large number of documents from the process, including witness statements, hospital records, interviews, media coverage, and more. Elliot had the idea to run some natural language processing on lots of this data in order to extract some more conclusions from it. Could we see if the police had colluded on their testimonies in court? Perhaps we could perform sentiment analysis and compare the media’s opinion to that of the families of the victims?

But we quickly realised that the data was not in a useful format. Most of the documents were images of text from a typewriter. Not something a computer can read, and importantly, impossible to search.

Pivoting!

We decided to change our ‘hack’ to be full-text search for the documents. This means not just searching for document titles and the short descriptions provided for each one, but searching all of the text inside the documents. This could be hugely powerful.

How do you extract the text?

With great difficulty. We had already downloaded over 3,000 of the documents (there are over 19,000 in total) so we had a copy of every document relating to police statements. But these were PDFs containing images. The first stage was to prepare them for OCR (Optical Character Recognition).

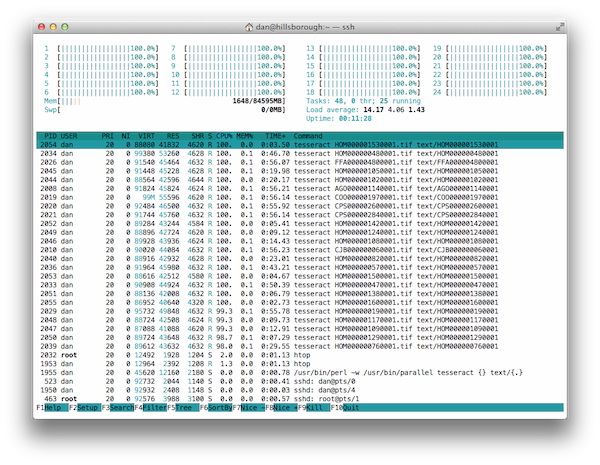

ls *.pdf | parallel gs {} "tifs/{.}.tif"

ls tifs/*.tif | parallel tesseract {} text/{.}.text

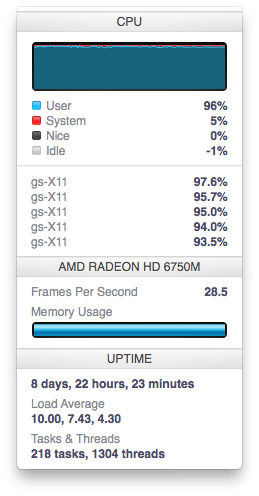

We used Ghost Script to generate images from the PDFs. Originally we had wanted to use ImageMagick, but it didn’t support creating multi-page TIFFs from multi-page PDFs. Also, I hadn’t known about GNU Parallel before this, but it turned out to be hugely useful for us, and managed to saturate the CPU on my laptop.

This ended up taking almost an hour, but we ended up with a folder full of TIFFs ready to run through an OCR program to extract the text, but when we tried this, it was taking 30s or more for each document. With 2 hours to go on the hack, this clearly wasn’t fast enough.

After trying and failing to get the OCR program Tesseract installed on a university server where we didn’t have root privileges, we turned to the ‘cloud’ and got the biggest server that Digital Ocean (the VPS provider that Elliot and I both use). 24 Intel Extreme cores. 96GB of RAM. SSD storage. That should be enough right?

We ran this for about 3 hours in total, and it used all of the processing power it could with every core at full usage until about 2 hours in when we neared the end of the documents. In the end there were just a few really large documents (of around 800 pages each) left to finish while we were waiting for our turn to present.

Finally, we shoved the whole lot into Apache Solr which does great text search and enabled us to index and query really quickly.

Why this is Important

It wasn’t until we were putting some slides together at the last minute for our presentation that we really realised how important full-text search and plain text copies of the documents were. They weren’t just something we had wanted to do our natural language processing to make some interesting graphs and statistics, this was a lot more than that.

With over 19,000 public documents, that are almost impossible to search, how can anyone really know what happened at Hillsborough? It’s far too much information for a single person to process, but it needs a single person to go through them in order to make the connections required to explain what went on.

The inquiry had a conclusion, so we know the official story of what happened, but it didn’t satisfy everyone. Families want to know one thing, while the police force want to know another, and with the report and it’s evidence being as inaccessible as it is, is it really what the public needs?

By creating a searchable database, anyone can now browse the documents, in a way that lowers the barrier to finding information and forming conclusions. We’re proud of what we accomplished, even if it wasn’t our original goal, and we hope to work with the Hillsborough inquiry to make this available in the future to everyone.

Thanks to everyone at Rewired State for putting on the event, to the judges for their generous award of the “thing that Harry likes most” prize, to everyone sending their kind comments on Twitter, thanks to the Hillsborough Inquiry for taking the first steps into opening up their data, and thanks to my teammate Elliot for his help on this project.