Requirements change for the better

I’m an armchair space enthusiast – I like to watch new launches but I know very little about rockets. Recently there’s been a lot of renewed interest in landing on the moon which is very exciting, and also a lot of press coverage of NASA’s Commercial Crew programme returning manned spaceflight capability to the United States.

Between these two advances, there have been many pointing out the decades where we as a society, and the US in particular, were going backwards. The Moon landing was in the 60s, but we stopped going in the 70s, and the US lost the ability to launch humans into space in 2011 at the end of the Shuttle programme.

There’s a theme in modern software engineering that feels very similar. In 1968, Douglas Englebart demoed live collaborative document editing on a computer, alongside a video conference session with colleagues in another town. This was revolutionary at the time, in a similar way to the moon landing, but it took us until 2003 to get Skype and 2005 to get Writely which became Google Docs.

We have computers that are far faster now than even 10 years ago, and yet they don’t do much more. I regularly see comparisons of feats of software engineering from decades past compared to the seemingly trivial struggles we have with our modern tooling.

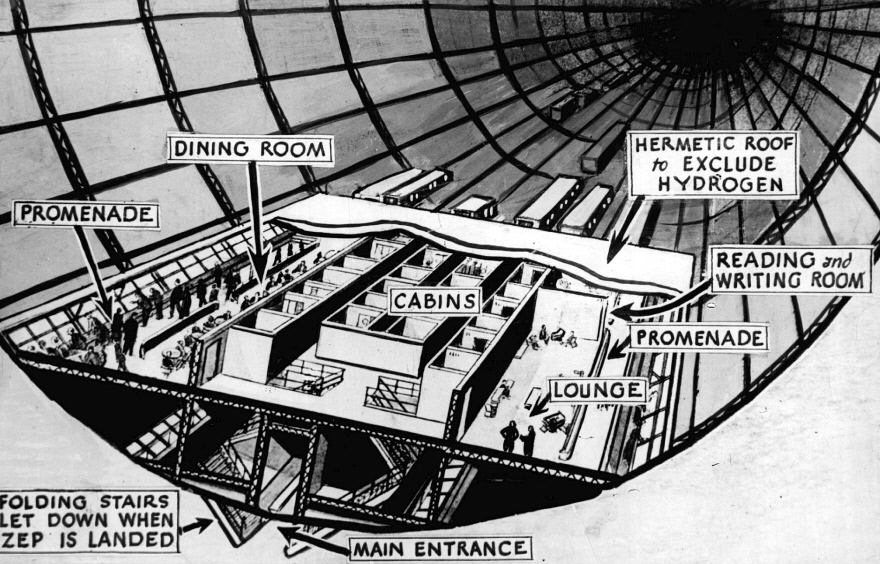

Let’s take a brief diversion to talk about a great new invention that’s going to take the world by storm. It can transport large numbers of people in luxury. No more cramped aeroplanes, here you can have a bed and dine in the onboard restaruant, wander along the promenade. As the cutaway below shows there’s even reading room and a writing room.

But it doesn’t stop there. It can stay aloft for days, is very fuel efficient, and the military models could even be equipped with hangers to deploy and retrieve their own squadron of smaller planes for defense or reconnaissance.

This is of course an airship. By many measures airships sound like great idea, in the 20s and 30s they were the Next Big Thing. So why did it take us until around 2010 to get back to large cabins in the sky on board the luxury Airbus A380?

Well airships have a fatal flaw, quite literally, in that they use hydrogen for lift. Hydrogen in extremely flammable, and airships eventually lost their appeal after many were brought down in flames by the smallest of sparks. Even those using inert helium for lift proved remarkably unsafe. Finally, airships are also slow. They could take several days to cross the Atlantic, where a regular commercial jet would take only 6 hours.

What does this have to do with manned spaceflight or software engineering? Airships illustrate the error in the criticism we saw earlier. On paper, airships seem great, or at least much better than what one might think looking at the number of airships on the departures board at Heathrow today. But we know they aren’t.

Manned spaceflight is in a similar position. The Apollo programme ended and we lost the capability to get to the moon, but we also ended a programme with a nearly 1 in 10 fatality rate, missions that could only send 3 men at a time (and they had to be men), mostly test pilots, who had to measure in a fairly small height range, to the moon on rockets and in spacecraft that weren’t reusable in any way.

We moved on to the Shuttle. A vehicle that could carry 7 astronauts and significant payloads. The Shuttle was big enough to build the ISS, and deploy and maintain the Hubble Space Telescope. It could also be re-used, even if doing so cost $1bn and required months of work. 42 women travelled to space on the Shuttle. But perhaps most importantly of all, the Shuttle proved to have a much lower fatality rate, at roughly 1.5%.

The shuttle programme ended in 2011, and all the focus is on companies like SpaceX and Boeing. While there’s still much to be proven by these companies, the 48 successful landings by SpaceX, and the fact that they are refurbishing and re-using Falcon 9 boosters rapidly and for a tiny fraction of the cost suggests that this leap forward could be as impactful as the last.

How about software engineering? When Douglas Englebart performed his demo in 1968 it was astounding, and in some ways still is today. But like manned spaceflight many things that are less visible have improved significantly in the last 50 years.

Our computers are far more secure, no longer sharing memory between processes, having strict separations between operating system and programs. Our networking isn’t single point-to-point leased cables as it was in Englebart’s demo, it’s an infinitely configurable high speed network connecting nearly every computer on the planet on-demand at low cost. The “video conferencing” in the demo was also not what we’d consider video conferencing now – it was a TV signal displayed on top of the computer’s output, not passing through the computer at all, whereas modern video conferencing allows us to precisely control our video, and stream on commodity hardware rather than TV cameras.

There is waste in modern software, but it’s also far more accessible and accomplishing more today than it ever has. High level languages like Python may run far slower than it’s possible to run, but they are accessible enough that they are taught in school at a young age. They might waste our fantastic computing resources, but they also let us develop software faster than ever before.

It’s easy to say that things aren’t as good as they used to be, and it sounds good in a headline, but when you encounter tidbits like this have a look for where our standards and requirements have changed.

Are we really going backwards, or are we just unwilling to accept the level of quality we had before? Are we really wasting our resources, or are we having a far greater impact than before? Have we really lost something, or have we realised that there are more important things we could be doing that might not fit neatly into a headline or sound bite.